Françoise Hardy: A Melancholic Farewell to the Yé-yé Icon

In a poignant farewell, iconic French singer Françoise Hardy has departed this world at the age of 80, as announced by her son, Thomas Dutronc, on Instagram. With her passing, an emblematic figure of the 1960s era bids adieu, leaving an indelible mark on the annals of music history.

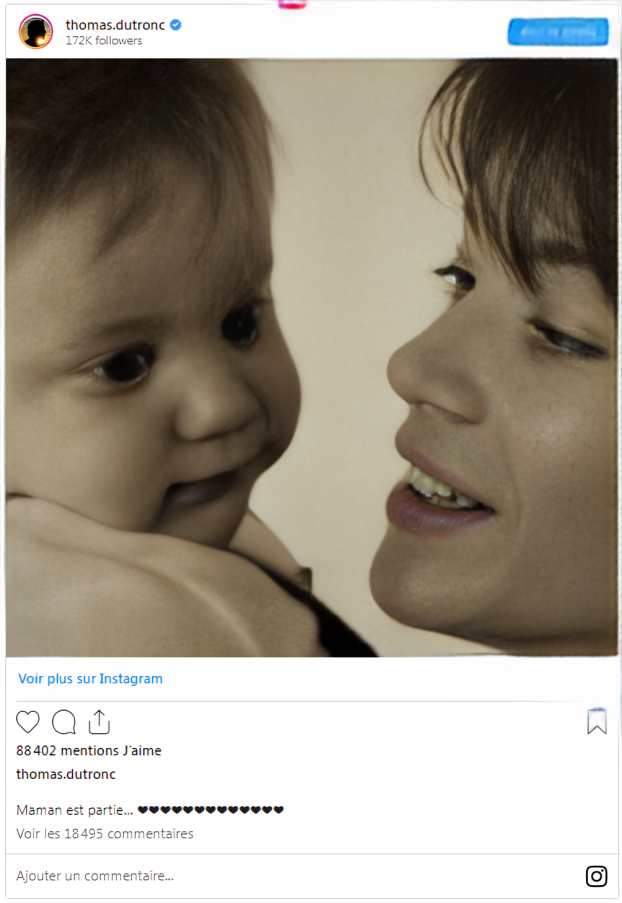

How does one bid farewell to such a luminary? After a prolonged battle against cancer, Françoise Hardy has taken her final bow. Her son's heart-wrenching words, "Maman est partie..." (Mom has left us), echo across the digital realm.

Hardy was never one to conform to societal expectations or seek approval at all costs. Her candor and unwavering spirit often manifested in interviews, where a simple "Non, pas du tout" (No, not at all) would redefine the narrative, a testament to her profound self-awareness and authenticity.

In recent months, Hardy had been increasingly open about her struggles. A cancer of the pharynx was slowly consuming her essence. In a heartbreaking confession to Paris Match last December, she shared, "Since my recent radiotherapy sessions, I've been unwell, with my right eye blurred and painful, and my right nostril constantly blocked. My mouth and throat are drier than ever. It's a nightmare..." Resigned and weary, she expressed her desire to "depart to the other dimension as soon, as quickly, and as painlessly as possible."

Yet, Hardy had previously defied death's grip, surviving a harrowing fall, three months of hospitalization, and a persistent lymphoma that plagued her for fifteen years. Her resilience inspired awe, though she humbly deflected any notion of personal combat, attributing her recovery to the efforts of medical professionals.

With her passing, a unique emblem of the yé-yé era fades into memory, joining the ranks of luminaries like France Gall and Johnny Hallyday. However, Hardy's melancholic allure set her apart from her contemporaries, who reveled in the carefree anthems of adolescent love.

While Sheila joyfully sang "L'École est finie" (School's Out), Claude François frolicked to "Si j'avais un marteau" (If I Had a Hammer), and Sylvie Vartan envisioned herself as "la Plus Belle pour aller danser" (The Most Beautiful to Dance), Hardy's debut hit, "Tous les garçons et les filles" (All the Boys and Girls), concealed her inner turmoil beneath her iconic fringe. She portrayed herself as an eternally solitary heart, wandering "seul par les rues, l'âme en peine" (alone through the streets, soul in anguish).

This melancholy permeated her entire career, spanning 28 albums and iconic songs like "Message personnel," "Mon amie la rose," and the deceptively breezy "Comment te dire adieu." As she sang in her 1967 cover of Brassens' "Il n'y a pas d'amour heureux" (There Is No Happy Love), Hardy seemed destined for a life tinged with sorrow.

At 17, Hardy harbored profound insecurities, deeming herself unattractive and "laborious" in her songwriting efforts within the confines of the Petit Conservatoire de Mireille, a musical television program where she honed her craft under the watchful gaze of cameras. This creative outlet provided an escape from a bleak existence marred by a tumultuous upbringing.

Born on January 17, 1944, in Paris, Hardy was an "enfant de la honte" (child of shame), a "bâtarde" (bastard), the product of an adulterous liaison between a young woman and a man twenty years her senior, already married. Her mother became a single parent, a circumstance Hardy would later recount with biting irony, referring to her birthplace as "en haut de la rue des Martyrs, dans une impasse" (at the top of Rue des Martyrs, in a dead end).

Raised by her adoring mother and a grandmother who despised her, Hardy's isolated and complex-riddled childhood fostered a tendency to view the glass as half-empty, a trait that would persist throughout her life.

Fortunately, Hardy's artistry resonated with audiences, propelling her to stardom and capturing the admiration of Anglo-Saxon icons like Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, and David Bowie. Yet, her two great loves eclipsed even these accolades: first, Jean-Marie Périer, the photographer of the yé-yé era, and later, the enigmatic Jacques Dutronc, with whom she shared a relationship as complex as it was sincere.

While the public envisioned an elegant couple, the reality was far more intricate. Dutronc remained elusive, philandering, and solitary, even after the birth of their son, Thomas, in 1973—a child caught between a doting mother and an independent father. Hardy accepted this dynamic, utterly devoted to her "mari" (husband), as she affectionately called him, even as he eventually retreated to Corsica. "Over there, my husband leads a much healthier life than mine. He's had a companion for fifteen or twenty years now, which suits me just fine. My only fear is that she might leave him," she confided candidly in 2015.

"Françoise is the shortest path between thought and speech," her longtime collaborator Jean-Marie Périer once remarked, a testament to Hardy's uncompromising authenticity. She embraced her right-leaning political views amidst predominantly left-wing artistic circles, her passion for astrology from the 1980s onward, and her health struggles, meticulously documented in her 2015 book, "Avis non autorisés..." (Unauthorized Opinions...).

In an April 2021 interview, Hardy acknowledged her declining health, confiding, "I want to be there for those I love, but when I'm in too much physical distress, the fear of suffering in an even more unbearable way, with no hope of getting better, fills me with anguish. I deplore France's lack of humanity in not legalizing euthanasia. Even Spain and Portugal have done so."

In her later years, our communication was primarily through email, yet she remained responsive. On her 80th birthday, January 17th of this year, we inquired about her wishes, to which she poignantly replied, "Well, given my poor state of health, if I were to pass to the other side in 2024, like everyone else, I would hope for a swift and relatively painless transition, even though the pain of separating from my son and his father would be infinite."

Previously, when asked if she feared death, Hardy had responded with a resolute "no." "I'm mostly thinking about the immense grief of leaving my son, of causing him pain. But I much prefer to die than to endure unbearable conditions that drag on. And in the back of my mind, I've always harbored the idea that there's something after."

With her passing, the music world mourns the loss of a singular voice, a muse whose melancholic musings transcended the buoyant spirit of the yé-yé era, forever etching her name in the annals of French cultural heritage.

Lire aussi

Latest News

- 15:45 Barcelona and Inter clash in UEFA Champions League semi-final

- 15:38 Vietnam marks 50 years since war's end with the US

- 15:10 Morocco highlights investment potential at 'Morocco Now' conference in Madrid

- 15:08 Catalan companies seek guidance on U.S. tariff response plan

- 14:37 Iran, UK, France, Germany to Hold Nuclear Talks on Friday

- 14:30 Feijóo and Mazón's cautious reunion amid energy crisis overshadows EPP congress in Valencia

- 14:07 Iraqi vice prime minister delivers Arab summit invitation to Moroccan sovereign