-

11:30

-

10:30

-

08:00

-

14:20

-

15:50

-

18:34

-

18:26

-

17:30

-

13:30

Modern Moroccan architecture and the enduring urban class divide

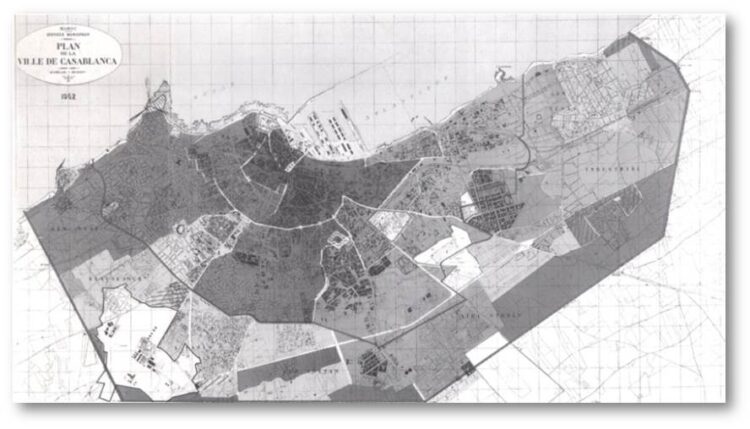

During the French Protectorate (1912–1956), cities such as Casablanca, Fez, and Rabat were redesigned to enforce a physical and social separation between Europeans and Moroccans. European districts were constructed as symbols of prestige and authority, featuring wide boulevards and grand squares, while the medinas remained narrow, densely populated, and largely unchanged. This urban planning created a dual economy and entrenched social disparities, a pattern partially mitigated but also exacerbated by the rise of shantytowns.

Architects like Henri Prost, appointed in 1914 by General Lyautey, implemented metropolitan plans that emphasized order and visibility, effectively reinforcing colonial hierarchies. Michel Écochard’s 1946 development plan further reshaped urban spaces, abolishing communal land practices and cementing foreign influence. These structural interventions, often overlooked in historical and architectural discourse, weaponized city layouts to enforce social exclusion and maintain rigid hierarchies.

Independence in 1956 granted Morocco political sovereignty, yet colonial urban frameworks persisted. Modern Moroccan architecture, while striving for innovation, has largely mirrored global trends prioritizing visual spectacle over the social and environmental needs of communities. Luxurious developments, high-rises, and shopping complexes contrast sharply with under-serviced working-class neighborhoods, highlighting the continued marginalization of local residents.

Casablanca exemplifies this urban inequality. Neighborhoods like Anfa, Maârif, and Racine are preferred by wealthy Moroccans and expatriates for their safety, modernity, and community appeal, while middle and working-class families face overcrowding, limited access to infrastructure, and rising housing costs. Vacant diaspora properties worsen the housing crisis, as they are often reserved for tourists or left unused. Government programs like the Direct Housing Assistance Program (Daam Sakane) aim to provide affordable housing but often locate new homes on city outskirts, inadvertently reinforcing spatial inequality.

Modern architectural trends, driven by cost-efficiency and global aesthetics, further alienate local communities. Traditional craftsmanship and culturally resonant designs are frequently sacrificed to maximize profits, sidelining the social and communal functions of urban spaces. Scholars like Christopher Alexander argue that such globalized approaches neglect human needs and social cohesion, turning architecture into a tool of abstraction rather than community building.

Some historians argue that colonial planners, such as Lyautey, intended spatial separation to protect local culture rather than enforce racial hierarchy. However, the structural effects of these policies, combined with entrenched socioeconomic inequalities, suggest a deeper, intentional design to maintain colonial control. As Frantz Fanon noted, the colonial city created “two worlds,” a dynamic replicated in many post-colonial societies. While there are no simple solutions, recognizing these historical and structural causes is essential for guiding reforms toward more equitable urban development.